Woofter, James, 1991, Job’s Temple A Gilmer County Landmark, Goldenseal, Mountain Arts Foundation, pp. 58-64. Copied with the permission of Grace Woofter.

Job’s Temple

A Gilmer County Landmark

by James Woofter

Job’s Temple, a Gilmer County landmark, is a log cabin church, one of few remaining in West Virginia. At one time. perhaps when Gilmer was part of Virginia, there were log churches scattered through each county. Most have been lost through neglect or replaced with frame and brick buildings. There was one such church located at Pisgah, only three miles away, but it was destroyed by fire over a hundred years ago. It is from the Pisgah Church that Job’s Temple originated. The congregation split in the mid-1850’s over the same wrenching and divisive issues which were breaking America apart at that time. A number of people from he Pisgah Church, some of whom had children buried in its cemetery, preferred the Southern side of the national debate. They decided to build their own house of worship.

Construction of the new church was begun shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War. When the great conflict began building work appears to have been suspended as some members of the congregation entered military service. As far as it is known, little if anything was done towards finishing the project until after the war ended in 1865. Meanwhile West Virginia had become the 35th state. Hence Job’s Temple, begun under the jurisdiction of one state, was finished under that of another.

The land on which the log church was built was donated by Jonathan and Margaret Bennett. The original site consisted of “one acre and nine poles, more or less, ” according to the deed recorded in the Gilmer County Courthouse. Apparently construction was begun well before the church body owned the land, because the site was not deeded by the Bennetts until 1872. In 1913, and again in recent years, more land was donated so that the church grounds now comprise some four acres.

Job’s Temple was organized as a Methodist Episcopal Church, South, at DeKalb, Gilmer County, State of West Virginia. The original trustees were Levi Snider, N. W. Stalnaker, William H. Stalnaker, James A. Pickens, Edward T. Gainer, Salathiel G. Stalnaker, and Christian Kuhl. Of that number, three were later buried in the church cemetery.

Job’s Temple stands near Job’s Run, a minor tributary of the Little Kanawha River. The fact that the church was named for the stream, and not the other way around, is documented in the writings of the Reverend E. B, Jones, pastor from 1889 to 1893. The Reverend Jones wrote that his church took its name ‘from the a small run on which the Temple is situated, the run being named in honor of Job Westfall, who was the first settler on the run.” Another account identifies Westfall as an itinerant preacher and says that he was active in founding Job’s Temple.

the church was built mostly with yellow poplar logs, hand-hewn and hand-dressed, all well over a food square. They were chamfered and notched in the manner then customary and seem not to have slipped appreciable over the decades. The big logs were chinked and daubed with local clay mud, consistent with construction procedures in use at the time. As far as is known, all but the bottommost log on the lower side are original. One can only wonder at the difficulty of lifting the 30-foot logs into the interlocking position they hold today.

The roof was made of wooden shingles or clapboards. The outside measurements of Job’s Temple are approximately 24 by 30 feet. Many of today’s houses have recreation rooms of greater dimensions.

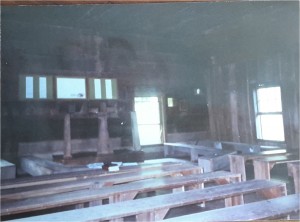

Inside, the ceilings and walls were made of hand-planed yellow poplar boards, many of which are almost two feet wide. A representative of a Charleston architectural firm, when examining the church several years ago, noted that the wall boards were the finest example of hand planing she had ever seen.

Job’s Temple is laid out much like other country churches. A slightly elevated platform in the front part of the sanctuary served as the pulpit. On it three wooden stands, or lecterns. were placed. One was used by the minister. The other two were used by other participants in the worship service or served as lamp stands when artificial light was needed. Two of the three stands now in the church are believed to be original. Oil lamps were also placed on shelves along the wall.

The benches used when Job’s Temple was first built were made of split logs with wooden legs driven into holes bored into either end. None of the original seats remain. They have been replaced by backless plank benches made in the more recent decades by local artisans. The two angled. “mourners’ benches: which now flank the alter were probably also not original, but they are believed to resemble those actually used when the church was built.

When it was active, Job’s Temple was a member of the Conference of Southern Methodist Churches. That membership ceased in 1912 and the church did not have a regularly assigned pastor after that.

Over the years Job’s Temple has been used for a variety of purposes aside from that of a church. In former times, singing schools were conducted there each year. Traveling singing masters taught the shape-note method of singing to the members of Job’s Temple and the other area residents. One such master was Bill Bush. Singing schools permitted the introduction of new songs into the community, in that age of no radio or television and very few newspapers. The schools also served as social gatherings for local people. My mother attended singing schools at Job’s Temple in her youth and remembered them fondly.

The sturdy church building gave shelter when needed. One new family even set up housekeeping in Job’s Temple. In other instances local families whose homes had been ravaged by floods on the Little Kanawha sought temporary refuge there.

More recently the old church has served more as historic shrine and local landmark than as an active facility. It comes to life twice each summer. In June all the Belles, the older ladies representing West Virginia counties at the State Folk Festival at Glenville come to the temple for a religious service concluding the three day festival. And of course the big annual home-coming occurs each August.

Several ministers serves as “pastor of the charge” at Job’s Temple during its half-century of active service. They included Joseph Jenkins, J. S. Pullen, William Virden, E.R. Powers, Hazel Williams, C.S. Walmsly, and others. The Reverend Jones is said to have held a protracted meeting that lasted six weeks and reaped 160 conversions to the faith.

The church rolls included Gainers, Pickenses, Bealls, Stalnakers, and other prominent family names of the area. You will find the same names on the gravestones in the church yard. The first grave in the Job’s Temple cemetery was that of Margaret Stalnaker Pickens, who died February 18, 1870, at the age of 18 years. She is said to have requested to be buried in the “new cemetery.”

The Pickenses and Stalnakers, representing some of the earliest settlers in Gilmer County, have more of their people buried at Job’s Temple than do any other families. Thirteen members of the Pickens family and 35 Stalnakers rest there. Lambs, Maxwells, Riddles, and Woofters are among those who lie beside them. Like any country graveyard, the Job’s Temple cemetery includes people who were born, lived, and died in the neighborhood, as well as others who spent their early lives there, left for a time, and were returned for burial. There also are some who came from elsewhere, lived out their lives in the community and were buried there.

Some 60 years ago Job’s Temple had fallen in to a serious condition of disrepair due to lack of use and poor maintenance. Writing in The Glenville Democrat, the late Ed Orr described his first visit: “Surrounded by weeds and approached only by a steep winding path, I found the log church which is the only spot in Gilmer County to earn mention in the historical section of the Blue Book of West Virginia this year. After noting the unkempt surroundings, the thing that impressed me was the sturdiness of the structures in the days long gone by. Slowly, though surely, the building that once was a community center of another century is now disintegrating – crumbling away in spite of all the efforts that have been made to preserve it.”

Local poet Carmen Rinehart Moss captured the scene more poignantly in a poem from the same era. Moss’s last stanza runs as follows:

Job’s Temple- built to honor Him

Who once five thousand fed.

Now stands deserted by the road

And guards its sacred dead.

Moss had grown up on Grass Run, two miles from Job’s Temple, and her mother had once belonged to the congregation. Her 1930 poem no doubt speaks for many others with similar roots.

Fortunately the demise of Job’s Temple foreseen by Orr and feared by Moss was not to be. Instead, Ella Maxwell and Lona Woofter, two local women who had worshiped at the Temple in their youth, joined forces in the 1934 to consider what could be done to save the historic building. By then the roof was badly damaged and some of the original ceiling boards had rotted. The fence surrounding the site was down in various places and both domestic and wild animals roamed the cemetery at will.

Maxwell and Woofter organized a movement to restore Job’s Temple. In 1934, they started the treasury with $16.86 , which they had solicited from individuals – mostly in dimes, nickels, and pennies. These were Depression times, remember.

Soon a group of local people went to work to restore the historic building. They put on a new tin roof. They repaired the floor and ceiling. They put in new windows and did numerous other things to preserve the old structure. All this was done by donated labor.

The first Job’s Temple homecoming organized to celebrate the success that had been achieved, was held at the church on August 14, 1936. A loosely-knit organization known as the Job’s Temple Association was formed at that meeting. Charles “Boone” Maxwell was elected its first president, and Pearl Pickens its first secretary.

The Reverend Levi Gainer delivered the sermon at the first Job’s Temple homecoming. In the afternoon B. W. Craddock, local attorney, and Carey Woofter, the husband of Lona and registrar at Glenville State College, spoke briefly of the community’s early settlers and of those who lay in the cemetery. The collection for that day was $20.16.

As time passed, more improvements were made around the church and grounds. Concrete steps were installed as part of a walkway from the adjacent state highway to the church. The late Henry Fiser of Pittsburgh, whose wife’s parents are buried at Jo’s Temple, set concrete headstones and footstones for the graves that did not already have markers. He also cast and installed the concrete fence poste that are still in place around part of the site. A concrete speaker’s platform was built near the entrance to the church. A maintenance and upkeep program was begun for the building and grounds.

In December 1978, the Job’s Temple Association was incorporated, thus formalizing the organization that had functioned unofficially since 1936. The corporation is now responsible for the continued repair and upkeep of Job’s Temple, administering a program designed, insofar as practicable, to preserve the historic property in perpetuity.

In 1979, Job’s Temple was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, pursuant to the provisions of the National Historic Preservation Act. The log church is the only site in Gilmer County to have achieved the distinction of being placed on the National Register.

When work was first begun to rescue the Job’s Temple church and grounds, there were 67 graves which had only unlettered fieldstones. We were fortunate to find among the papers of the late Carrey Woofter a plat of the cemetery which he and Ella Maxwell had drawn about 1917. From that paper we learned who was buried in many of those unidentified graves, the relatives and friends of whom had left Gilmer County or long since died. People still living in the area helped us identify the graves of those who had died after 1917 and whose names consequently were not on the plat. Combining the information, we were able to identify all the graves in the cemetery except six. The Job’s Temple Association authorized the purchase and installation of granite identification markers for the 67 graves.

So Job’s Temple still stands as it has for well over a century, guarding the sacred dead, as Carmen Moss’s poem has it. Perhaps more important is the continuing service to the living, as a rallying point and a symbol of our Gilmer County heritage.

You can see that best at homecoming time. The local motel fills up, as people flock in from far away. That’s the way its’s always been, according to Stanley Pickens, current president of the Job’s Temple Association. “My out-of- town relatives – brothers, sisters, and cousins – would be coming home from a long way for the Job’s Temple gathering,” he recalled. Visitors stayed with local relatives in the old days, but the homecoming spirit remains the same.

And a special spirit it is.” I remember as a young boy growing up in Gilmer County the excitement and anticipation of the second Sunday in August, ” Stanley says. “I hope that these young people have the same feelings I had as a boy.”

I am looking for Carmen Rinehart Moss’ poem about Job’s Temple. Thank you.

This is a wonderful and symbolic place. I visit whenever I am able–the Association takes such great care of this history.